By Robert Paul Wolff, continued from here

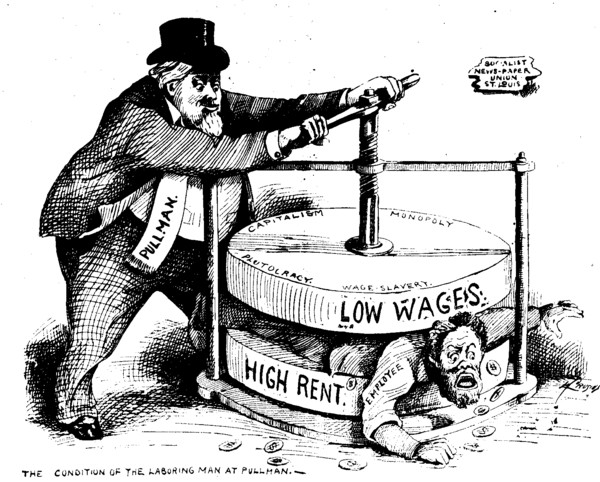

[…] So I went back to Marx’s text and looked again. And there it was, as plain as day. The workers in a capitalist economy get only a portion of what they produce by their skill and labor, because by a long historical process of expropriation, they have been denied ownership of their own means of production – of their tools, of their machinery, even of their skills – until all they have left is their labor, which if they wish to live they are compelled to sell in the marketplace as though it were a commodity whose natural price is the cost of its reproduction. Why don’t farmers get to eat all the food they grow, after setting aside what is needed for seed? Because they do not own the land and the farm tools. Why don’t factory workers get to wear the clothing they make or to sell it to buy the food they need? Because they do not own the wool or the cotton or the thread or the machinery with which they turn these materials into clothing.

How, I asked, can we capture this situation in a set of formal equations that explains exactly how the workers are getting screwed and simultaneously explains why in a capitalist economy it seems as though the workers are getting a fair return for their labor? Here is what I came up with:

If we look carefully at the price equations in a simple capitalist model, we see [I go into this at length in my article] that formally speaking, labor is not modeled differently from any other input on the left side of the equations. Oh, to be sure, we use the letter L or l to stand for “labor” but that is just a labeling convention, not a formal distinction. No wonder everything we show about labor also can be shown for iron or corn or cloth. They are all represented formally in precisely the same way in the equations. But in the real world, there is a fundamental structural difference, which we ought to be able to capture mathematically.

Consider: The ideology of capitalism says the worker is a legally free producer of the commodity labor. OK. Then in our system of price equations, let us have an equation for the labor producing industry as well as equations for the corn, iron, and cloth producing industries. [Notice that in this approach, there is no need to formulate labor value equations.] Now, in each equation, there is a term [1 + π ] which stands for the profit mark-up. [π or the Greek equivalent of p is the one standard symbol for the profit rate.] And the profit rate is the same in every industry because competition and the movement of capital in pursuit of the highest rate of return equilibrates the profit rate. If a capitalist who makes high end jewelry for sale to the carriage trade is making 5% on his invested capital while a junk dealer is making 8%, then the quality jeweler will move his capital out of gems and into junk, because in a capitalist economy, all any good honorable capitalist cares about is his rate of return, not the social acceptability of his product. [You understand that I am laboring mightily to communicate the math in as palatable a fashion as possible.]

But there is a big problem with the labor sector. The worker, who is in this model a labor manufacturer, cannot move his capital to a sector with a better rate of return, because his capital is his body, and the only way he can cash in his capital and move it is … by cashing it in, which is to say dying! So the worker, who by an historical process of expropriation has been deprived of his true capital, his tools and skills and land and raw materials, is compelled to remain in the labor producing business. In other words, the worker has no choice but to get a job working for a capitalist.

When we set up the equations along these lines, with a separate rate of return in the labor equation, we find that the prices, and hence the rates of return, in the other sectors are skewed up by virtue of the fact that one huge sector, the labor sector, is frozen and cannot move its capital to compete [and thus drive down the prices and the rate of return] in all the other sectors.

How much does the labor sector lose by this structural rigidity? Well, not surprisingly, what the labor sector loses is exactly mathematically equal to what all the other sectors gain. In short, profit in a capitalist economy is the extra value taken from the workers by virtue of the fact that they have been deprived of their ownership of their capital. Which is to say:

CAPITALISM RESTS ON THE EXPLOITATION OF THE WORKING CLASS, MADE POSSIBE BY THE HISTORIC EXPROPRIATION OF THE WORKERS. And all of this can be [and was, by me] demonstrated mathematically.

That, my friends, is the connection between exploitation and expropriation.

Originally posted here

Close

Close