By David Ruccio,

Unless we change our tune and resolve to fundamentally alter the way the economy is organized, we’re going to have to face up to the problem that’s been haunting the United States for decades now: growing inequality.

And it’s only getting worse.

Part of the problem stems from the increase in market concentration in the United States. According to a recent research paper by Joshua Gans et al., the rise in mark-ups by large U.S. corporations is a two-edged sword: it increases the prices consumers pay but, at the same time, rewards shareholders. The problem is, the ownership of corporate stocks is more unequal than consumption—and it’s been getting more unequal in recent decades. Thus, the majority of Americans are forced to pay higher prices for the goods they consume but they don’t own much in the way of corporate equity—and the distribution of income, which was already obscenely unequal, is made even worse.

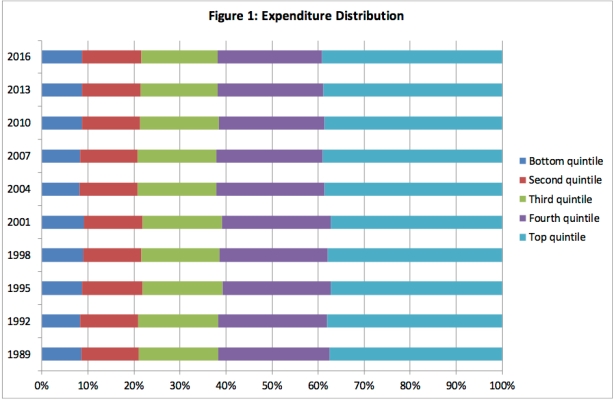

For example, the distribution of consumption expenditures is profoundly unequal but has remained relatively stable over time: the 20 percent of families with the lowest incomes accounted for 9 percent of all expenditure in 1989, the same figure as in 2016. The 20 percent of families with the highest incomes comprised 38 percent of all expenditure in 1989, rising to 39 percent in 2016.

Meanwhile, the ownership of corporate equity, which was grotesquely unequal in 1989, has become even more unequal over time. The lowest-income fifth of families had 1.1 percent of corporate equity in 1989, and still only 2.0 percent in 2016. By contrast, the highest-income quintile had 77 percent of corporate equity in 1989, and even more—89 percent—in 2016. In other words, corporate equity is about 13 times as concentrated as expenditure.*

The authors estimate that the rise in market power in the United States has lowered the bottom 60 percent income share (from 21 to 19 percent) and raised the income share of the top 20 percent (from 61 to 64 percent).*

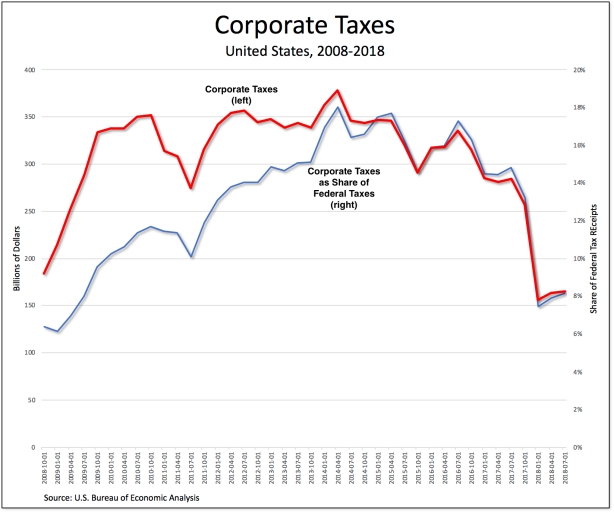

The other, more recent cause of growing inequality is of course the 2017 Republican tax cut, which has allowed large corporations to reshuffle their books, reduce their federal tax obligations and use their higher retained earnings to increase stock buybacks and the dividends they pay to already-wealthy individuals (who, in turn, have been able to use their higher post-tax incomes to purchase more shares in U.S. corporations).

As is clear in the chart above, corporate taxes—in both absolute terms (the red line, measured on the left) and as a share of federal tax receipts (the blue line, on the right)—have declined precipitously since the tax cuts were enacted.

Meanwhile, as readers can see in the chart above, the dividends corporations are paying out to the richest Americans (as well as foreign stock owners) continue to hit record highs—thus adding fuel to the fire of rising inequality in the United States.

Both increased corporate concentration and last year’s tax cut have widened the gap between the haves and have-nots in the United States. That much is clear. But Americans have to face up to a much more fundamental problem, both in days gone by and now, which neither antitrust measures nor repealing the tax cut will fix.

The fact is, the surplus created by American workers is appropriated and distributed not by them, but by the boards of directors of the corporations where they are employed. Those who do most of the work have no say in what is done with the surplus they create—nor do they receive the proceeds, either in the form of increased pay (which has barely budged in recent decades) or stock dividends (which have soared).

Unless Americans resolve to tackle that problem, the economic “seas between us braid” will continue to roar.

*But the authors also make clear that rising concentration is only part of the problem: “The rise in income inequality over the period that we study has been considerable, and even in the absence of market power, incomes would be more concentrated in 2016 than they were in 1989.”

**According to my own calculations, in 2014, the top 1 percent owned almost two thirds of the financial or business wealth, while the bottom 90 percent had only six percent. That represents an enormous change from the already-unequal situation in 1978, when the shares were much closer: 28.6 percent for the top 1 percent and 23.2 percent for the bottom 90 percent.

Originally posted here